Before I get into it, I know the meaning of trust has eroded over the past several decades. The particular admixture of credence, confidence, and faith we invest in certain individuals who earn it – at least among the public – has seen a decline, noted in the first world from the United States to New Zealand. Then there’s the coextensive problem of a deepening dearth of such individuals, at least in our country.

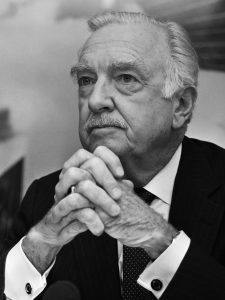

Where have you gone Uncle Walter? A nation lifts its bloodshot eyes to you…

I’m not even saying he’s like the typical neighborhood pastor, who, as one of the nation’s clergy, in the past, was among the most trusted members of our society. They may still be, in individual instances, and certainly there are whole intact communities for whom the church is the defining social construct and context for meaning, spiritually and in the quotidian.

However, recent polls by Gallup and an organization called NORC – the National Opinion Research Center – 3 out of 4 Americans rarely or never consult clergy. Trump does comparatively better, with a recent aggregate approval rating as compiled by FiveThirtyEight of nearly 43%. It’s doubtless erroneous (and laughable) to call it trust, but he certainly has tapped a national mood among a significant number of followers, when a phrase he uses in one of his Tweets about a member of Congress becomes a chant and catchphrase for an arena full of rally attendees just two days later.

The factors that contribute to his disapproval rating of over 52% are the stuff of suspicion and wariness: his mendacity, his outrageous public behavior, his lack of discipline and gravitas. All qualities that would have rocked the confidence of the American people as a whole had any been demonstrated by “Uncle Walter” back in the day. And even Trump’s adherents openly cite and recognize his shortcomings, but they approve his positions on the issues and conflicts he so breezily tweets about on a daily basis. He is, whether instinctively or deliberately for strategic reasons, the spokesman, if not now the avatar, of opinions and attitudes held by a significant number of Americans.

Members of the electorate have always been reluctant to articulate all of these opinions, and thereby have been hard to identify, quantify, and validate by polling. Trump legitimizes those positions by openly espousing hard views on always sensitive facets of the American character: the degree of openness and acceptance of our people and our society to other than unquestionable exemplars of the majority demographic of white, working and middle-class, established, and native-born – or, more accurately, anyone who identifies with such a categorization. He makes it all right not only to embrace these views as beliefs, but vociferously to ensure they are recorded for posterity, and accorded the status of news for broadcast to the world.

Fifty-one years ago, Walter Cronkite visited Vietnam and witnessed the condition of the city of Hue, virtually annihilated during the so-called Tet Offensive. The result was a rare moment of editorializing about a war that Cronkite personally had supported, even while doing his utmost to ensure the reporting of it by his News division would be balanced and unbiased. What he saw, which, as fact, annuled what President Johnson had been reporting to the American people, led Cronkite to reverse his views on the war, and to announce formally, “We Are Mired in Stalemate.” And from that broadcast can be measured a turn in the tide of the public opinion of the United States as a whole, which previously had endorsed the prosecution of the war.

President Johnson’s equally famous reaction to the Cronkite reversal, and the likely impact on the political climate leading up to the presidential elections later the same year, led him to announce he would not seek a second term of his own, saying “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost Middle America.”

It is the same Middle America that is fueling the uptick in approval ratings of President Trump, that is, since his renunciation of the four Congresswomen of color, and the one in particular, Ilhan Omar, who is a naturalized citizen, formerly of Somalia, whom he has publicly vilified and exhorted to go back to where she came from—the ultimate shibboleth thrown in scorn at the immigrant seeking a new life in America.

Whatever the evolved mutation from a position of trusted reporter to a position of evocative rabble-rouser of a man undeniably and virtually universally in the public eye because of the power of mass media (which certainly now includes, if it is not dominated by, the internet), it takes a Cronkite or a Trump to crystalize feelings and attitudes otherwise previously inchoate and perhaps even subconscious in the minds of many.

If so, and however I may have misidentified or mischaracterized the transmutation of the nature and the agency of the process in the course of the last 50 years, the phenomenon remains the same. And the reasons I fear are immutable. The American people are not disposed either to introspection or to contemplation with the goal of insight into what the increasingly ubiquitous vehicles of reportage of the world in which they live maintain as a live feed—however circumscribed an existence they attempt to fashion for themselves. When a voice of authority—or of some other order of authenticity that resonates with the innermost needs and fears of people in a fog of self-imposed cluelessness—speaks, the greatest comfort derives from joining the chorus of assent. However horrible the consequences.